| Top | Master Plan Contents |

Chapter 3: The Park Today

INTRODUCTION

Despiteseveraldecadesofdecliningsupportand,

in some instances, public misuse, the noticeable

degradation that occurred in the seventies and

eighties is no longer occurring. Although this is

good news, no doubt owing to the closing of

most of the park roads to automobiles, the park

remains at a critical juncture. The numbers of maintenance and support staff have not increased

and remain at a minimal level, performing mostly

routine duties and dealing with emergencies.

Typical of many urban parks, decades of cutbacks

have increased the demands on reduced numbers

of park maintenance staff, who are no longer able to maintain the standard of care that was

anticipated by the park designers.

These effects are, overall, gradual and generally

less noticed by the public because relatively less of the park is used in recentyears.

Sugar maples in decline around the seldom used circuit drive,

for instance, are a less

apparent problem than an accumulation of

trash in the picnic area would be. Certain

activities, especially organized games, attract

large groups of people; however, visitors often

contend that less exclusive activities and

regular event programs for families and

individuals are still largely missing from the

park. These and the issues described in the

following pages are the challenges that

Cadwalader Park faces in its second century.

| Top | Master Plan Contents |

REGIONAL LINKAGES

At 109.5 acres, Cadwalader Park is the largest

urban park in the City of Trenton, and therefore,

is a significant open space for the city. The

Delaware and Raritan Canal State Park, a seventy-mile recreational corridor and greenway,

passes through the park and provides a link to

several other large open spaces. Washington

Crossing State Park, about six miles upriver along

the Canal, is one of two nearby parks along the

Delaware River, the other being Washington

Crossing State Park in Pennsylvania. StacyPark, a

city park, and Hamilton-Trenton Marsh, a county

recreation area a few miles downriver, could

eventually be linked to Cadwalader by a sequence

of proposed and existing river greenways.

Plans for a linear park and regional greenways

would connect Cadwalader to points north and

south along the Delaware River. The D&R Canal

State Park already links Trenton as far as the

town of Frenchtown in the northern direction.

The Delaware & Raritan Greenway is a corridor

preservation plan centered on the D&R Canal,

part of the Raritan River, and various creeks and

rivers that feed in to the canal. The National Park

Service is directing a plan for the Delaware River

HeritageTrail, a recreational and commuter

route that would link parks and open spaces

along the Pennsylvania and New Jersey sides of

the river. The East Coast Greenway, a proposed

regional greenway, would extend the Delaware

River greenway system south to Philadelphia.

The proposed Assunpink Greenway would

connect Cadwalader Park to the North end of

Trenton via local parks and streets.

| Top | Master Plan Contents |

NEIGHBORHOOD SETTING

Cadwalader Park lies approximately at the center

of the West Ward of the City of Trenton. The

oldest adjoining neighborhood, Hillcrest, to the

north of the park, was originally part of the

Cadwalader/McCall estate and was subdivided for

development by George Farlee. Conceived as a

“streetcar neighborhood,” the Hillcrest neighborhood

developed slowly because the Trenton

trolleylines were not extended to this area until

1904. Cadwalader Heights, to the east of the

park along Parkside Avenue, was planned by the

Olmsted office as a complement to the park, with

generous, curving streets and mature trees

(Figure 23: Cadwalader Park c. 1925).

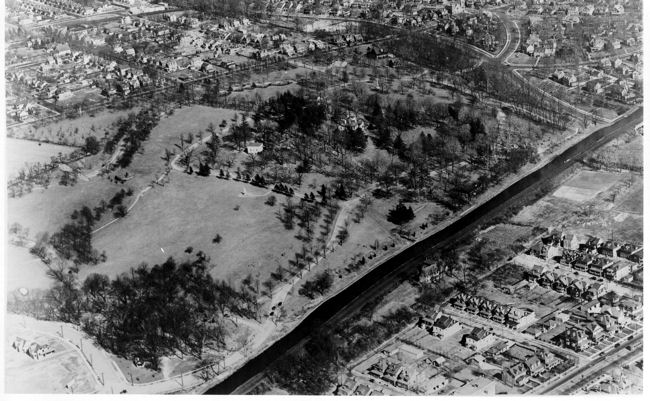

Cadwalader Place and Berkeley Square are two historic neighborhoods that lie south of Cadwalader Heights and appear on city maps around 1907. Parkside West to the south, was laid out on flatter land in the conventional city grid system beginning around 1900 (Figure 24: Cadwalader Park and West Trenton neighborhoods, c.1920s). Hiltonia, the neighborhood to the west, was the last to be developed, beginning around 1925.

Figure 23. Cadwalader Park c. 1925

Figure 24. Cadwalader Park and West Trenton neighborhoods, c. 1920s

The neighborhoods surrounding Cadwalader Park are a major constituency for the park. As such, they play a critical role in the current use and future vision for the park. However, the park is now and always has been a significant historic, cultural, and open space resource for all of Trenton.

| Top | Master Plan Contents |

PARK USE AND IMAGE

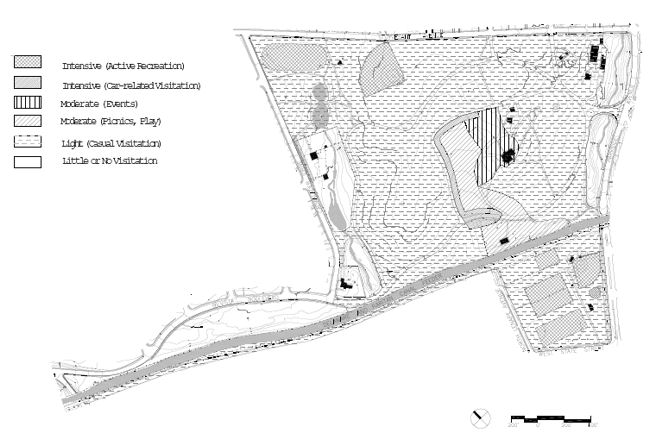

Scheduled and Event Use

The most intensive uses of the park are active recreation by organized groups such as Little League baseball and Men’s Unlimited basketball (Figure 25: Park Use Areas). The basketball games have drawn as many as 2,000 spectators to the lower recreation area. The softball and baseball fields, and the tennis courts, receive consistent and frequent use in good weather. Special event use is moderately intensive but occurs relatively infrequently within the park. Openings and shows at the Art Museum are a popular activity and can draw upwards of 200 people. The City also stages special celebrations and activities in Cadwalader that draw well over 1,000 people, such as the annual May Day and Halloween events. The park is also the location for a segment of an annual national-level bicycle race that takes place in Trenton. Isles, Inc., a local community development and environmental education group, conducts programs for a variety of user groups at Cadwalader Park, including day sessions for over 3,500 schoolchildren and family hikes on summer evenings. Parkevents, such as the Tree tour and annual May plant sale, are held in conjunction with citywide events. Isles has also proposed to rehabilitate the two-story animal barn as a permanent, year-round environmental education and interpretive center for the park. Ifcompleted, the facility would likely draw school groups and visitors from a greater regional base than at present.

Figure25: Park Use Areas

Group Use

The sports fields and courts in both the upper

and lower park are used on a daily basis in good

weather. The play ground and picnic pavilion area

is also used frequently by day care groups during

the week and families on the weekend. The

picnic pavilion and the sports fields receive the

greatest amount of group use. Groups over 25,

including wedding parties, families, church groups,

and sports organizations apply for permits from

the City, which guarantees them a date and a

location in the park. Permit use has increased

within the park in recent years.

Casual Visitation

The picnic grove, with it sassociated drives, is the most accessible area to vehicles and as a result receives the heaviest casual use of any park area. “Car-related” visitation —visitors who remain with their vehicles while in the park—is a daily use along Theater Lane and the circuit drive near the playground. On late afternoons in good weather, people arrive by car and park near the picnic grove, sometimes pulling picnic tables over to the cars and congregating on those. Car washing takes place along the circuit, mostly between the playground and the east ravine. Picnicking is heaviest on summer weekends and occurs mainly within the picnic grove. Visitors often stop to view the deer and geese in the deer paddock. Neighborhood residents walk, cycle or jog in the park, usually on mornings, evenings or weekends. The D&R Canal towpath brings visitors past and into the park, particularly on pleasant weekends.

Park Abuses

Cadwalader Park has remarkably little trashand

graffiti compared to many similar urban parks, due

partly to vehicle restrictions, which discourage

heavy use. Alcohol and drugs are reportedly

consumed within the park, mostly after dark,

occasionally openly during the day. Violence

occurs randomly and infrequently and, given the

relative infrequency of use, probably occurs

much less at Cadwalader than in more

urbanized locations in the city.

Perceptions of the Park

Cadwalader Park suffers from a popular

regional perception that it is not safe. During

community meetings, local residents emphasized that they felt quite safe in the park during

the day, although many are wary of being in

the park after dark. In the years prior to the

closing of most of the park drives, the park

gained a reputation for drug and alcohol use

as well as car racing and speeding on the

drives. This reputation has lingered despite

acknowledgment by representatives of the

Public Safety Division and the community that

the park safety is much improved. There was

common consensus at the public meetings

and among police representatives that the

need for improved security throughout the

park is critical.

| Top | Master Plan Contents |

EXISTING ENVIRONMENT

Geology

The area that is now Cadwalader Park is situated on an alluvial terrace of the old Delaware River. The river flow was greatly increased after the retreat of the Wisconsin glacier because of the huge volume of water resulting from tremendous quantities of snow and ice melting upstream. Coarse debris deposited by the river during large sediment flows included quartzose sand, cobbles and gravel. This debris, the Pennsauken formation, underlies the present-day surface soils in Cadwalader Park.

The surface soil soriginated from fine silts that covered the river bed after the glacial flows decreased. As the sediment dried, wind carried the silts to adjacent uplands and deposited it to a depth of two to three feet. This silty material forms the basis of the soils found in the park today.

Soils

Five different soils are found within the park.

Matapeake soils(MoB), derived from silty material

deposited by the Delaware River, are the most

extensive in the park. Matapeake soil is normally

well-drained, fertile, retains water and nutrients,

and occurs on moderate slopes throughout the

park. An eroded Matapeake soil (MoC2) is found

at the north end of the park on steeper slopes

surrounding the ravine and deer paddock areas.

Mattapex-Bertie soils (Mq) are found on in the

area of the Lower Gully athletic field. The lower

horizons of these soils are saturated with water

during the late winter months and are very acidic,

presenting severe limitations for planting. The

area between the Lower Gully field and the

upper pond is covered by Bucks soils (BuC), a

well-drained silty soil that developed from

deposits of red Brunswick shale. The area around

Ellarslie is covered by the Birdsboro series(BnC),

a fine sandy loam soil with a relatively shallow

three to four foot depth to bedrock.

Soil moisture is low throughout the park. With

the exception of one small sump (approximately

50 square feet in size) in the pedestrian footpath

at the north west corner of the site (near the

Gully field), no saturated soil conditions or poor

drainage were noted. The west ravine has a

flood-prone area and wetland vegetation is

present; however, the soil matrix does not

indicate hydric soil conditions. Wetland soils and

conditions were absent in the rest of the park as

well.

Topography

The entire park lies on a broad east-west slope, which drops eighty feet from Stuyvesant Avenue to the athletic field ssouth of the Canal. High points within the interior of the park are the Overlook, where the Roebling statue is sited, and Ellarslie, which sits astride a hilltop facing southwest toward the Delaware River. A broad shallow valley between these two hills was the location of the former bandstand and is the site of the present-day picnic grove.

Two streams, one on either side of the park, flow toward the river through fairly steep ravines. The Delaware and Raritan Canal feeder forms the western edge of the park for about two-thirds of its length. Grades along either side of the canal feeder are moderate to steeply sloped. Below the canal, on the south side of the park, the land flattens and is graded into athletic fields.

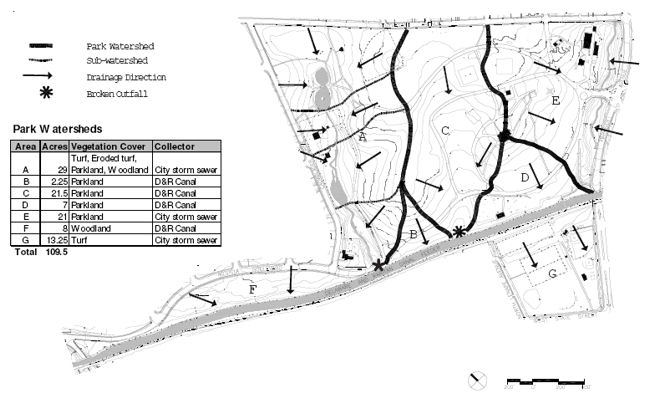

Figure26: Park Hydrology

Hydrology

The major watersheds of Cadwalader Park

drain either to the D&R Canal or to city storm

sewers before draining to the Delaware River

(Figure 26: Park Hydrology). Approximately

one-third of the park, or 32 acres, drains to

the west ravine and the city storm system.

Another 22 acres drains through the east ravine

to the city sewers. The rest of the park discharges

its surface flows directly into the Delaware and

Raritan Canal, which flows between the upper

and lower sections of the park. The watershed

boundaries were delineated and the runoff

quantities assessed in a technical report prepared

for this master plan, Tree Survey and Hydrologic

Assessment for Cadwalader Park.

The technical study assessed several major

indicators of rainfall absorption and runoff. Land

cover, topography, soil moisture, and surface

permeability were interpreted for each watershed

area. Visual assessments of the runoff patterns,

existing storm drain inlets, stream channels,

ponds, and the canal were completed. The study

also assessed bankstability, appropriateness of

channel width and depth, appropriateness of

existing man-made features, vegetative cover,

appropriateness of adjacent land use, non-point

source pollutant load inputs, meander patterns,

runoff patterns, and over all condition of the

feature.

General Conditions Two streams flow through the park, the west

ravine stream, which also includes the upper

pond and the lake within the deer paddock, and

the east ravine (Figure 27). The two stream

systems exhibit good channel stability with

relatively minor erosion, which is confined mainly

to the deer paddock and along the southernmost

portion of the east ravine. The infrastructure

surrounding these streams, however, is in fair

condition and deteriorating. Vitrified clay pipes |

Figure27. East ravine and bridge |

Figure 28. Upper Pond |

Upper Pond The upper pond is hourglass shaped and varies in depth from 12 inches to a few inches where sediment accumulation is greatest (Figure 28). The main source of water for the pond appears to be a city water line, with storm drains and local runoff a secondary source. During summer months, the pond appears stagnant, with large algal blooms covering much of the surface of the pond. The pond banks are stone and are structurally intact; however, soil compaction caused by foot traffic is present at the pond edges. The weir outfall of this pond was, at the time of observation, jammed with woody debris, leaves and trash. Severe erosion adjacent to the outfall threatens the stability of the weir and appears to be caused by surface overflows from the pond. |

West Ravine within Deer Paddock

This section of stream was once channeled into a stone and concrete flume, which has since failed. Fallen stone walls above the lake create debris jams that force water to be redirected out of the channel, eroding stream banks. The erosion problem is exacerbated by the lack of vegetation within the paddock. Animal grazing and trampling has prevented tree canopy coverage over the stream and reduced the number of tree roots available to stabilize the soil.

Deer Paddock Lake The lake is entirely within the animal paddock and |

Figure 29. Deer Paddock |

Figure30. Historic early 1900s photograph shows west ravine looking much the same as today |

West Ravine below Paddock The west ravine is surrounded by a well-established

riparian woodland (Figure 30). The

stream is relatively steep for most of its length,

is geomorphologically stable and in good

condition. Concrete and stone walls that were |

Water Quality

Water quality testing performed for the west

ravine in September 1998 above, below and

inside the animal paddock are as indicated the

presence of high levels of bacteria, including

fecal coliform and fecal treptococcus. Bacteria

were present in the upper pond in levels

eight times that which is considered safe for

human contact. Bacteria counts were about

three times as high as this within and below

the animal paddock. The upper pond is

probably contaminated by sources outside the

park (which need to be investigated), while

both the large number of waterfowl, and deer

paddock runoff, play a major role in the

contamination of the stream and lake.

Water tests were not conducted on the east ravine; however, water quality problems were evident. A strong oily odor is present as well as an oily sheen and blackened rocks. Litter and floatable debris are present in the upper reach and increased quantities of trash and debris were observed immediately after rainfal levents.

EastRavine

The stream originates from a large culvert

under Stuyvesant Avenue and extends through

a ravine along the eastern Park boundary to

the Canal. The channel is geomorphologically

stable and is in good condition. The most

severe erosion has resulted in four to six feet

high bank cutting on the lower portion of the

ravine. Storm drain outfalls carrying water

from Parkside Drive have also caused minor

slope erosion. Pedestrian activity in the form of

desire line trails is also present in the ravine.

The woodlands here are less dense than on

the west side of the park, creating a situation

where the ravine is vulnerable to loss of one

or two major trees.

| Top | Master Plan Contents |

STORMWATER MANAGEMENT AND SOIL COMPACTION

Stormwater Management

There are numerous small storm sewer systems throughout the park, which convey stormwater from local or park roadways to the streams or the canal. Two storm sewers drain into the UpperPond, leaving it vulnerable to occasional heavy storm flows. An older storm sewer system passes through the picnic grove and discharges directly into the D&R Canal. Another older system, which extends up Theatre Lane to the Ranger Station, discharges to the east ravine. The Lower Recreation Area has a new drainage system that runs parallel to Lovers’ Lane and discharges into the existing City storm sewerline in West State Street.

Most of the park’s storm drain inlets appear to be

functioning adequately, although many of the

structures are filled with debris. All storm drains

should be cleaned and inspected to determine

their condition. Runoff threatens the east ravine

south of the main entrance. Continued erosion of

the bank will cause deep gully formation and

could potentially threaten stability of the mature

(30" DBH) white oak that holds this part of the

bank in place. Damage to the forest canopy,

slope, and adjacent park road would be significant

if this tree were to be undermined.

Soil Compaction

The slopes in the park and the accompanying soils on the mare normally not susceptible to erosion, provided there is adequate vegetative cover. Soil compaction observed throughout the park, however, has caused loss of vegetation in heavily used areas. This compaction can be attributed to off-shoulder vehicle parking, maintenance vehicles, intensive foot traffic, or animal grazing.

Soil compaction from parked cars is evident along Lovers’Lane, especially near the athletic fields. Vehicle traffic has also compacted the lawn adjacent to the inner loop drive at the picnic grove, as well as the grass adjacent to the circuit drive from the playground to the Parkside Avenue exit. The area around the ranger pavilion and comfort stations is also compacted, probably due to vehicle traffic, as well as the roadway edges around the bollard locations. The latter is caused by security and maintenance vehicles circumventing road barriers.

Areas that show soil degradation from pedestrian activities include the playground, the exterior of the deer paddock, the slopes leading into the woodlands adjacent to the paddock, the area around the lily pond, and the southside of the entrance drive at the Parkside Avenue entrance. Several desireline trails were observed through the park. The most severe problem exists directly across from the foot bridge north of the canal. Vegetation on the slope is almost nonexistent due to excessive foot and bicycle traffic. The steepness of the slope, combined with the high volume of use, is causing severe erosion. Other areas of concern include slopes leading from the basketball courts to the neighborhood near North Lenape Avenue and the slopes in the east ravine. Foot traffic in these areas is causing significant damage to the soil and vegetative communities. Trampling and overgrazing of surfaces by animals within the deer paddock has also caused severe soil compaction. Since most of the west stream as well as the lake are within the paddock, the streambanks and lake have been pockmarked by hooves and stripped of vegetation (Figure31). Without protective wetland vegetation and cooling shade, the lake has lost most of its biotic quality and cannot support native populations of amphibians, fish or insects. |

Figure 31. Eroded, muddy bank |

| Top | Master Plan Contents |

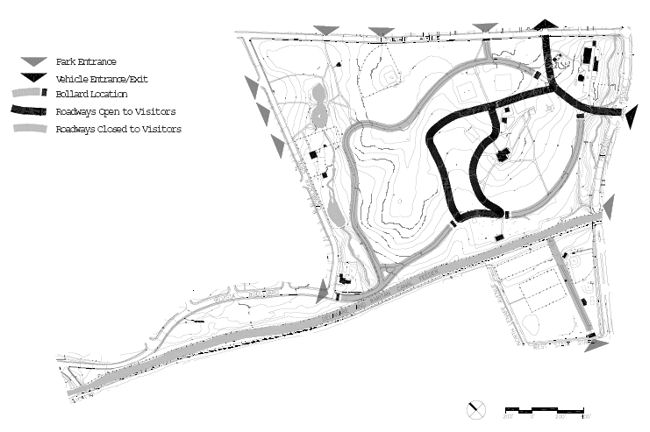

CIRCULATION

Access and Circulation

Cadwalader Park still retains asignificant feature of the 1891 plan, namely, the circuit drive, which was constructed around the perimeter of the upper park much as the Olmsted firm had envisioned. A large part of the original stone edging and gutter remains, although asphalt pavement has been laid over most of the gutter (Figure32). The graceful curves of the roadway as the drive traverses the park slopes still provide a sense of unfolding and changing landscape views. |

Figure 32. Early postcard shows cobble gutter at walkway

edge which is still in evidence |

Figure33. Road through the park today |

Most of the circuit drive, however, is now closed to visitor cars and the roadway is used exclusively by pedestrians, police, and park vehicles (Figure 33). Bollards, connected by a removable chain, block entrances at Stuyvesant Avenue and Hilvista Boulevard as well as access points from the park’s system of interior drives (Figure34: Existing Vehicle Circulation). The park’s inner circulation consists of two roughly parallel drives that form a one-way circulation pattern. Theater Lane begins about five hundred feet from the park entrance and travels past the Ranger Station and the former bandshell area, turning left around the picnic grove and continuing on to connect with the circuit drive. A second drive on the opposite side of the picnic grove functions as the second half of the inner loop. It begins near the playground and curves up the hill around Ellarslie to the Comfort and Ranger stations. From here, drivers can continue back around the picnic grove or head toward the exit on Parkside Avenue. Cars may also exit the park via the circuit drive instead of heading up the hill to Ellarslie. |

Figure 34. Existing Vehicular Circulation

The Parkside Avenue gate is the only entrance to the park used by visitors entering by car. Visitors may also exit using the Maple Avenue extension, an entrance that is often used by maintenance vehicles. Several other entrances to the northwest corner of the park, which access gravel drives, are used occasionally by police and people bringing equipment to the playfields.

The Lovers’ Lane entrance to the lower recreation area is closed to vehicles but, in practice, is often kept open for park service vehicles. People using the playing fields and courts frequently drive through onto the lane when the entrance is open during the day.

Parking

Visitor parking is limited to parallel parking along the inner drives. Theater Lane and the Ellarslie drive are striped and can accommodate about sixty cars. About thirty-five more can park along the exit section of the circuit drive. There is one designated handicapped space at Ellarslie.

No parking is designated within the park for the lower recreation area; however, day visitors often park on Lovers’ Lane when the entrance is left open for maintenance use. Visitors normally use street parking on neighborhood streets when games are in progress.

Most of the permanent staff members park near the cottage and maintenance garage, near the Parkside Avenue entrance. Administrative staff and visitors on business park in front of the cottage, while maintenance staff park behind the cottage or next to the garage.

Street parking is available along the outside

perimeter of the park. Cadwalader Drive can

accommodate about 70 cars. Another 50 cars

could park on Stuyvesant beginning at the corner

with Cadwalader Drive up to Beechwood

Avenue. Local residents utilize street parking east

of Beechwood. An additional 24 cars could park

on Parkside, south of the canal.

Two schools adjacent to the park may offer

opportunities for event parking. TheJoyce Kilmer

Elementary School north of the park has a

parking lot with 44 spaces. The lot is accessed

from Whittlesley Avenue and is surrounded by a

chain link fence. The gate is locked when the

school is closed. The Arthur J. Holland Middle

School on West State Street has a parking lot

with 65 spaces at the rear of the school. A

smaller lot near Lenape Avenue has space for

about 12 cars (see Table 4 in Chapter 4 for total

existing parking availability).

Walkways

It appears that no systematic walkway system was ever implemented at Cadwalader Park. The early aerial photos show two prominent east-west paths that no longer exist (Figures 23 and 24). One path leads from the turn in Theater Lane to the deer paddock on a direct line below the Roebling statue. Another path parallels the D&R Canal on the park side of the canal.

The existing pedestrian paths are located mainly at the perimeter of the park and around Ellarslie. Many of them are short paths that connect to the circuit drive, which is presently the only pedestrian route between the east and west sides of the park. Asphalt walks that connect the abandoned Bear Pit and Comfort Station to Ellarslie have greatly deteriorated and diminish the setting for the museum.

There are a number of walkways leading from the northwest perimeter of the park to the pond and circuit drive. These have retained their original stone edges, even where the gravel surface has become grassed over.

Paths leading from the upper park to the lower park in the vicinity of the play ground are actually only well-trodden desirelines (Figure 35). Users have scrambled up and down the canal terrace slope causing a large trampled and eroded area directly above the canal bridge. Other trampled paths lead from neighborhoods to the recreation facilities in the lower park. |

|

| Top | Master Plan Contents |

UTILITIES

The City of Trenton water and sanitary sewer departments service Cadwalader Park. PSE&G provides electrical service for park lighting and the buildings within the park.

The storm water system is discussed in this report under Hydrology. Further discussion, and a diagram of the existing utility lines, are provided in a technical memorandum prepared for the master plan, Traffic, Circulation, Parking and Utilities Assessment for Cadwalader Park.

Potable Water

The potable water system in the eastern

portion of the park consists of two mains that

terminate at hydrants in the park, and four

water lines that serve individual or building

groups. These are summarized in Appendix D,

Park Utilities. Since the water systems are

below ground, and consist of several mains that

enter from City streets and terminate within the

park, an inspection of the water lines was not

possible. The dead-end configuration of the lines

is also a maintenance problem due to the

inability, under this arrangement, to isolate leaks

as they occur.

Recently, park staff discovered a well near the Civil

War monument. Although it is possible that this

originally served Ellarslie, no detailed information

is available at this writing regarding this feature.

Sanitary Sewer

The City Sewer Department maintains two sewer mains coming from Cadwalader Drive and Hilvista Boulevard. There is an additional sanitary line along Parkside Avenue that ties into the line that services Ellarslie and other park buildings. A visual inspection of this line is difficult, since the line has slotted manholes with trashpans underneath which block the interior view of the manholes. The Superintendent of the City Sewer Department indicated that this line is prone to root blockages.

| Top | Master Plan Contents |

VEGETATION

Overall Trends and Patterns

The McCall-Farlee estate was already noted for its fine specimen “oaks, pines, beeches, vergreens and cypresses” prior to its acquisition by the City in 1888. Significant numbers of trees were planted in the early years of park development. Park records indicate that 8500 trees were reserved for planting in the park in 1893. It is likely that over 300 of the trees planted within the first 25 years of the park have survived, as evidenced by diameters of 30 inches or greater, and it is also likely that the approximately forty trees over 40 inches were present when the Olmsted team first viewed the park.

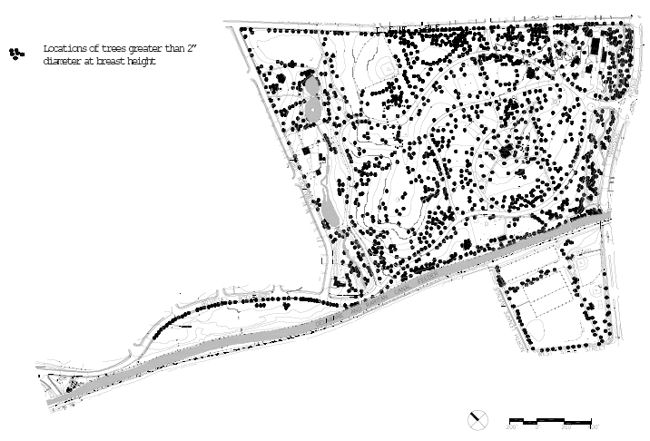

The extent of tree canopy increased dramatically from the beginning to the end of the twentieth century, as is evident in a comparison of the Olmsted 1891 plan with the recent tree mapping shown on Figure 36: Extent of Tree Canopy 1998. The rate of tree planting, however, slowed greatly after the war years– fewer than fifty trees were planted in the decades prior to 1975. The current planting program has increased the pace of tree replacement, memorial planting and other plantings, but there is no overall plan or system in place to direct either the species or the location of new plantings.

Figure36. ExtentofTreeCanopy, 1998

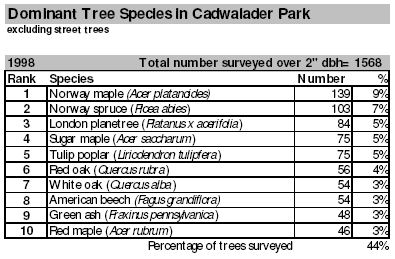

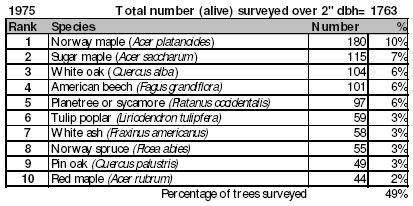

Note: A recent planting of sweetgums along Hillvista Blvd would place this tree at number five on the list; given the decline of smaller trees in the park due to mower damage these trees were not counted.

Table 1. Dominant Tree Species in Cadwalader Park |

The 1891 Olmsted plan, like his plans for Prospect and Central Parks in New York, relied on the creation of long views across open, rolling meadows that contrasted with more densely planted park edges. Over the years, tree plantings in Cadwalader have closed many of the long vistas and open meadow effects envisioned by the Olmsted design. Park visitors who stray from the roadways and established spaces have related a feeling of disorientation within the park. Clusters of trees have effectively blocked natural high points, such as the Overlook, that might otherwise provide a prospect for views (Figure 37).

Current Tree Inventory Since the park’s trees had not been studied in detail for over twenty years, an inventory was conducted as part of this master plan to determine the health and species diversity of the park vegetation. The results have been tabulated in the technical memorandum Tree Survey and Hydrologic Assessment for Cadwalader Park. |

Over 1,500 (1,568) trees were documented by the tree inventory. The survey utilized an integrated field approach to evaluate major forest canopy including tree genus and species, species diversity, andlocation. Each individual tree in Cadwalader Park was assessed for physical characteristics such as form; condition of central leader; presence of disease or environmental damage from ice, wind, and lightning; and overall health. Trees were rated for form based on crown height, canopy spread, appropriateness of species, and appearance. Structure was assessed based on condition of the central leader, crotch patterns, limb and bark condition, and presence of disease. A dead wood assessment was calculated and the overall specimen health rated. All data, including maps showing the location of each tree, is presented separately in the technical memorandum. As part of the study, each tree was given a number and labeled in the field.

Cadwalader Park possesses three narrow areas of woodland, totaling around 27 acres, that occur along the two stream ravines and near the canal at the north neck of the park. The woodland areas were sampled to estimate the number of trees per acre and the average tree diameter at breast height (DBH). Trees 24 inches DBH and larger were recorded as part of the tree inventory. Woodland shrub and herbaceous layer species were also recorded, as well as downed woody debris and invasive or exotic plant cover. A forest structure value was calculated for each woodland area, which could eventually be used to inform woodland restoration.

Species Diversity

The dominant canopy species in Cadwalader Park consist of a variety of mostly mature maples, oaks, tulip poplars, American beech and more recent plantings of spruce. The most common trees found are: Norway maple, London planetree, Norway spruce, Tulip poplar, and Sugar maple. The most significant trend with regard to trees is the decline of the park’s major native deciduous trees (Table 1, Dominant Tree Species in Cadwalader Park). White oaks and American beeches show dramatic decreases since 1975. Although sugar maples still appear numerous, the numbers do not reflect the poor condition of a number of the mature sugar maples, particularly those along the lower circuit drive. The decline of the native trees is paralleled by a dramatic increase in the numbers of Norway spruces and London planetrees (the latter were counted together with native sycamores in the previous survey). The tree most commonly planted in the past two decades, the Norway spruce, is neither a shade tree nor a tree that was originally recommended by the Olmsted firm for the park.

Species diversity in the park has increased since

1975, when the Golden and Rogers study was

conducted. The 1975 survey documented 76

species, of which 14 were sparsely represented

(Golden and Rogers compare their numbers to

the 1946 survey which recorded 84 species). The

1998 survey notes 84 named species; about half

that number are either exotics or are not area

natives, and 11 are ornamentals. As the 1975

study noted, a number of species are represented

in the park by only a few mature specimens,

which could mean a future decline in diversity.

Street tree diversity is higher along Cadwalader

Drive and the northwest corner of the park than

along the rest of Stuyvesant Avenue, which is

dominated by London planetrees.

Tree Condition

In general, many of the park trees require attention. The important entrance vista from Parkside Drive to Ellarslie has many mature trees in need of maintenance or removal. Along the long allee of mature beeches that once created a canopy above Lovers’ Lane, many trees are missing and damaged. Canopy damage from wind and ice, as well as a decline in vigor due to age and excessive soil compaction, are evident in many of these trees. New plantings here consist exclusively of sawtooth oak trees, which have been damaged by close mowing practices. Newly planted trees in general show considerable damage on the lower bark from weed whips and mowers.

Woodlands

The woodland areas consist of a mix of mature

trees (+24" DBH) and sapling-size trees. The lack

of understory and shrub layers is a concern;

however, the woodlands are still rated as having

high value for preservation and possibly restoration.

Invasive ground covers, such as English Ivy,

are present in limited amounts in the lower

woodlands south of the animal pens. A large

number of Norway maples were recorded in the

woodlands south of the deer paddock and north

of the bridge at the Parkside Avenue entrance.

Norway maples are harmful to native tree

reproduction in woodlands because they

reseed readily and cast a deep shade under

which many other species cannot thrive. In

addition, they are considered allelopathic,

suppressing the growth of other plants through

the release of toxic substances in the soil.

Ornamental Plantings

Ornamental plants in the park include golden

raintrees, hybridcherries, saucermagnolias,

dogwoods and rhododendrons. Groves of tightly

spaced dogwoods have been planted near the

Upper Pond and on the hill south east of Ellarslie.

The locations of the ornamental trees do not

appear to follow a particular pattern, such as the

Olmsted practice of planting flowering trees near

path nodes or at the edges of woodlands.

Ornamental flowerbeds are concentrated in areas

of high visibility at the Parkside Avenue entry, the

Stuyvesant Gate entrance, and along the path to

Ellarslie. They appear well maintained. Although

many historic photos of Cadwalader Park show

ornamental flower plantings typical of Victorian

and early twentieth century parks, it is unlikely

that the plans prepared by the Olmsted firm

would have included such plantings.

| Top | Master Plan Contents |

BUILDINGS AND STRUCTURES

A full description of park buildings, structures, monuments, and recreation buildings can be found in a technical memorandum prepared for this master plan, Buildings and Structures Assessment for Cadwalader Park.

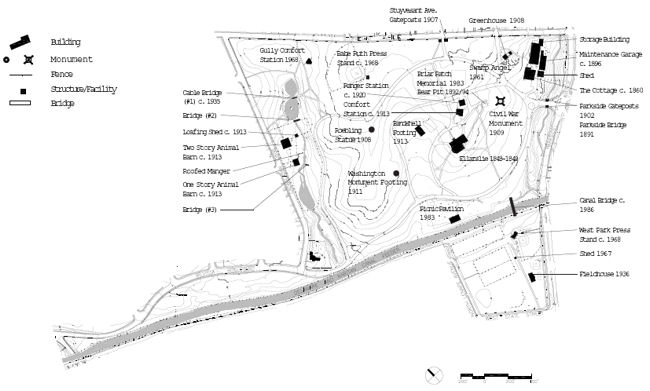

Buildings The buildings at Cadwalader Park reflect the evolution of the park’s development, beginning with its early function as the country estate of George Farlee (Figure 40: Buildings and Structures). Few buildings remain from the original estate. These include Ellarslie, the Maintenance Garage and the Cottage. Later structures, such as the Animal Barns, also remain. Several of the early park buildings from the 1920’s and 1930’s public works era remain, and are good examples of the period’s rustic, sturdy architectural character. Ellarslie, the Italianate villa that was the core of the original McCall-Farlee estate, sits at the crest of a ridge near the center of the park. For the past twenty five years Ellarslie has been the home of the City Museum and is administered separately from the rest of Cadwalader Park by the Division of Culture. Ellarslie had deteriorated greatly after years of functioning as a monkey house for the park. Restoration of Ellarslie as the City Museum is still ongoing. Ellarslie has been assessed as part of other studies and was, therefore, not surveyed in depth for this report.

|

|

Nearly all of the older buildings in the park are in need of significant repair (see Appendix D and E, Existing Buildings and Structures). TheCottage exterior is remarkably unaltered given its present use as park administration but requires immediate repairs to prevent further deterioration (Figure 38). The smaller of the two animal barns requires structural work and roof replacement to correct a severe roof sag condition. The Comfort Station is a well-proportioned park building that could be restored with modern facilities and ADA compliant access (Figure 39). The Field House is presently undergoing rehabilitation and replacement of restroom facilities, which will restore part of the historic park character to the lower athletic area. The Greenhouse consists of an old boiler room and glasshouse, both in poor condition. The structure is not historically significant and would not be feasible to restore.

The current Picnic Pavilion is the latest too ccupy the location near the canal (Figure41). Thefirst picnic pavilion, the “GrandLodge,” was constructed in 1902. It was 76’ by 54’ – over four times as large as the present structure (it is just visible above the canal treeline in Figure 23) and built of wood. The structure burned down and was replaced by the present concrete structure in the early 1980s.

Figure 40. Buildings and Structures

The current Picnic Pavilion is the latest to ccupy the location near the canal (Figure 41). The first picnic pavilion, the “Grand Lodge,” was constructed in 1902. It was 76’ by 54’ – over four times as large as the present structure (it is just visible above the canal tree line in Figure 23) and built of wood. The structure burned down and was replaced by the present concrete structure in the early 1980s.

|

|

|

| Top | Master Plan Contents |

RECREATIONAL FACILITIES

The Olmsted 1891 plan sited a “Boys Playground”

at the northeast area of the park, at

the corner of Stuyvesant Avenue and

Cadwalader Drive. In a use consistent with the

original design, sports fields occupy that part

of the park today. The Gully Field, typically

used for soccer, is an open field with back stops at opposite ends and bleachers to either

side.

The lower recreation area includes ballfields and a

new West End area basketball court with bleachers (Figure 46). Six asphalt tennis courts are

located below the basketball courts on the site of

the former park skating rink. They are maintained

in good condition. Six clay tennis courts are

located immediately below the asphalt courts

(Figure47). The clay courts require a higher level

of maintenance than asphalt courts but are fitted

out for play each year. A small building used for

tennis storage is in poor but repairable condition.

|

|

| Top | Master Plan Contents |

FURNISHINGS AND SIGNS

Park furnishings are ordinary, varied in style, and

do not contribute to the park’s overall historic

character. The benches and picnic tables are

regularly used on pleasant weekdays and on

weekends. Cadwalader has at least four different

combinations of wood, metal and concrete

benches. Thetables located at the picnic grove

are movable and are frequently relocated to the

shoulders of the park drives, in proximity to the

cars and car stereos. Park fencing is primarily

chainlink, located around the deer paddock,

between the playground and the park drive, and

around several of the recreational facilities. Iron

fencing may have been prevalent in the park at

one time, but was evidently removed during a

World War II scrap iron drive. (See Chapter 2.)

Park lights, which are square fixtures, are located

on sections of the circuit drive and along the

perimeter at Stuyvesant Avenue and Cadwalader

Drive. The recreation facilities are lit with large,

utilitarian athletic lights. The light fixtures at the

lawn bowling greens are nonfunctional. Street

fixtures, located south of the Parkside entrance

and at the lower recreation area, are contemporary long-necked fixtures. Substantial, attractive

new cast-iron traffic control fixtures have recently

been installed at the Parkside entrance, providing

an appropriate historic character at the front

door of the park.

Signs are also varied and mostly contemporary in style or regulatory, such as speed limit signs. A small sign at the Parkside entrance directs visitors to the Trenton City Museum. The remaining entrances are unsigned.

| Top | Master Plan Contents |

ANIMAL MANAGEMENT

A full description of Cadwalader Park’s animal

care facilities is contained in a separate technical

memorandum prepared for the master plan,

Summary Report on Animal Management for

Cadwalader Park. The memorandum is based on

field observations, investigation of veterinary

records, and discussion with the park veterinarian.

Site Description

The deer enclosure is a 4.6-acre parcel adjacent

to Cadwalader Drive, surrounded by a double chainlink fence eight feet tall. The enclosure

contains a shallow creek, which is dammed at the

southwest end, forming a pond. Two buildings,

noted on the plans as the Two-story Animal Barn

and the One-story Animal Barn, are located

within the enclosure. The smaller barn is open to

the air on one side and bedded with straw for

the deer. The two-story barn serves as storage

for animal supplies (e.g., hay, grain, medication,

etc.) and a variety of gardening, horticultural, and

groundskeeping equipment.

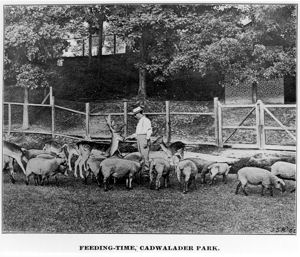

History

The park has housed deer species since 1895,

despite the recommendation from the

Olmsted firm that the deer be located outside

of the park (Figure 48). Fallow deer (Cervus

dama) were imported to the park before the

turn of the century and there have been deer

species at the park since this time. Records

show that the Fallow deer has been the

primary deer species housed at the park, but

white-tailed deer have been housed in conjunction

with the Fallow deer as recently as 15

years ago.

The deer population at Cadwalader has

fluctuated over the years, from more than 100

deer, to fewer then a dozen. At the time of this

report, the enclosure houses 14 Fallow deer, a

large number of wild and domestic fowl

(mostly geese, ducks, and pigeons), and a few

chickens. The present population of 14

animals consists of two adult males, six subadult

males, 1 adult female, and 5 sub-adult

females.

The birds are a significant part of the animal

population in terms of their physical impact on

the yard. Some of the birds may have originated

as Easter chicks or domestic birds. However,

with food and water in abundance at the site,

wild waterfowl have flocked here and remain

both as a nuisance and a health problem. The

birds foul the area with droppings and graze

continually for deer corn, trampling the yard and

the banks of the small lake.

Before the second perimeter fence was built,

people could and did feed the deer with

whatever they brought to the park. Public

contact with the deer has mostly stopped with

the double fence, which was built to satisfy

state and federal regulations that protect the

deer as well as the public. The fence is a large

visual and physical barrier to the Cadwalader

Drive side of the park; however, public sentiment

remains high for keeping the deer in the

park (Figure 49).

|

|

Animal Management

Diet

The present diet of the Fallow deer consists of

cracked corn supplemented with bran. The feed

is placed in elevated feeding troughs in three

locations within the enclosure. The deer are also fed grass hay, generally twice a week in hay

feeders. During wet weather, hay is changed

more frequently. A potable water source is

provided in 100-gallon open-air tubs, which are

cleaned once a day at servicing.

The geese, ducks, and chickens are fed (intentionally or not)

the same diet as the deer. Their feed

is poured from a five-gallon container in to an

open trough in one or two locations in the

enclosure. The waterfowl are also feeding on

food provided for the deer, resulting in a large

over population of geese and ducks.

Servicing

Animal fecal material is not removed from the

enclosure daily. If time permits, the servicing

personnel may remove excess fecal material once

a week, or otherwise, as needed. No established

protocol for area servicing is in place, but in

general, debris pickup and keeper area cleaning

occurs daily. Bedding hay is not removed as it

becomes soiled or wet; instead, dry hay is placed

over the old hay. Left over feed hay is not removed daily.

Health and Herd Management

The Park has a veterinarian under contract

who visits weekly and is on-call for emergencies.

The veterinarian is also responsible for

health issues that may arise, pre-shipping quarantine,

vaccinations, and animal purchases. The City

of Trenton Animal Control Bureau keeps records

of any animal deaths for a five-year period (there

have been no deaths over the last five years).

Other records are maintained by the veterinarian

and kept at the park administrative office. There

is no recognized breeding management program

in place and it is difficult to determine parentage

under the present system. Males and females are

not separated from each other, and offspring are

not separated from parents or adult deer.

Neonates remain in the herd.

Animal captures are conducted when necessary to remove deer in order to control the herd size. The deer to be removed are brought into the barn and herded onto a truck for transport to other zoo facilities.

| Top | Master Plan Contents |

SECURITY

The Division of Recreation has its own park rangers, who are hired on a seasonal basis to begin working in May. Six or seven rangers patrol at Cadwalader. The rangers are equipped with two-way radios and receive very basic law enforcement and CPR training. Rangers do not make arrests. Their main function appears to be traffic control and providing a security presence in the park. Although rangers are able to answer general inquiries about the park, they do not have a specific educational mission.

The Trenton Police Department is called in to

respond to specific problems as they occur.

According to the Chief of Ranger, the police

are in the park quite often to deal with incidents.

The police also patrol the area around the

park after 10:00 PM on a regular basis. When

needed for special events, the police will patrol

the park by car, on foot, or by bicycle.

The need for a greater security presence in the park was a major public concern expressed during the planning process. Interviewees and survey respondents, regardless of their reasons for coming to the park, frequently mentioned the need for continual, increased security. Maintaining both a physical police and ranger presence in the park appears to be of critical importance to much of the public. The Chief Ranger expressed a desire to have the rangers begin their stations in March or April, as soon as park visitors appear regularly.

| Top | Master Plan Contents |

EXISTING LANDSCAPE

MANAGEMENT

Organizational and Reporting Structure

The Department of Recreation, Natural Resources, and Culture has three main divisions reporting to the Departmental Director. The responsibilities of these divisions are described below.

Division of Natural Resources

This Division is responsible for the maintenance of parks, street trees, and special ornamental plantings for all 275 acres of parkland and all municipal property throughout the City of Trenton. In addition, the Division provides citywide landscape architectural services, site plan review, and operational support for special events. The Division of Natural Resources is also responsible for grounds maintenance of all senior citizens centers, City Hall, theTrenton Police Headquarters, and the City dog pound.

Division of Recreation

This Division operates four recreation centers, four Weed & Seed sites (after school programs), Park Rangers, summer and pool programs; and manages permit issuing for recreational programs. It is also responsible for several City run athletic leagues and helps coordinate volunteer-run leagues.

Division of Culture

The Division of Culture operates Trenton’s historical and cultural sites, including Ellarslie, Trent House, Douglass House, and Mill Hill Playhouse.

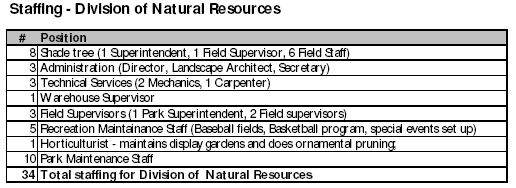

Table 2. Staffing– Division of Natural Resources (E. TimothyMarshall & Associates)

Staffing for Cadwalader Park

The Division of Natural Resources has a staff of 34, responsible for all 275 acres of parkland and all street trees throughout the City(see Table 2).

Basic maintenance tasks include:

• Mowing;

• Trimming;

• Playground maintenance —one person is more or less dedicated to playgrounds;

• Fence repair;

• Garbage pickup— two of the ten staff are dedicated full-time; and

• Animal husbandry—one staff person has responsibility.

Because of the diversity of tasks assigned to

Division personnel, there are no more than seven

full-time staff performing basic park maintenance

in the City’s parks. Including time allocations for

vacation and sick leave there are, on average, five

full-time staff assigned to daily park maintenance.

The city-wide full-time staff is supplemented by six seasonal staff in April and six more from July

to November, which averages six additional staff

from April-November. In addition to these

seasonal employees, workers also are drawn from

a Government Assistance Program (Welfare to

Work) and a small Community Service program.

Currently one full-time maintenance staff person

is assigned to Cadwalader Park. This staff member

is primarily responsible for mowing and is assisted

by a seasonal employee. The park receives some

additional staff time allocation for ball field maintenance

and leaf removal from other division crews.

Thus, there are approximately two staff plus the

inmate crew assigned to the park. The Division is

responsible for all park maintenance with the

exception of roadway lighting, which is maintained

by Public Service Electric and Gas Company

(PSE &G).

Natural Resources Budget

The total budget for the Department of Recreation,

Natural Resources and Culture is approximately $

3.1 million dollars ($2.5 million in salary

and $600,000 for materials, supplies, and equipment).

The Department also gets capital dollars,

however, these are largely project specific and are

completely separated from expense monies.

An expense budget of $2 million is allocated to the Division of Natural Resources and is used for salaries ($1.2 million), supplies, materials and equipment. A separate amount is allocated for capital expenditures. During the last five years, the average capital budget has been $500,000 annually.

| Top | Master Plan Contents |

ESTIMATED CURRENT

CADWALADER PARK MAINTENANCE

BUDGET (ANNUAL)

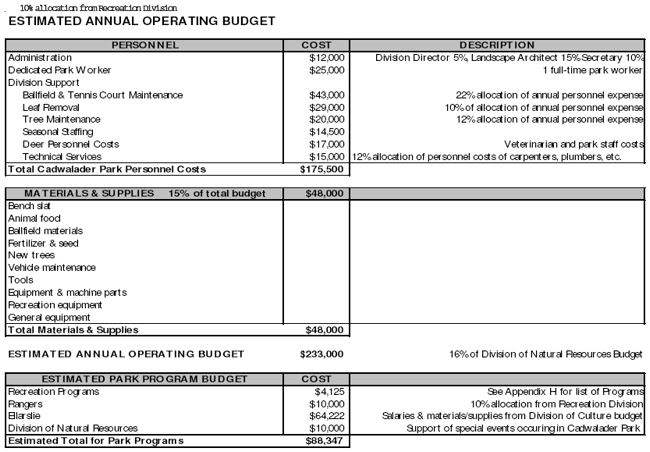

The proportion of the operating budget allocated

to Cadwalader Park is estimated to be $233,000

which represents about 16% of the Division of

Natural Resources’ total expense budget (see

Table 3). Most of this operating budget, approximately $175,000, is personnel costs, with

$48,000 going towards materials and supplies.

Cadwalader Park represents about 35% of

Trenton’s total park acreage and thus receives a

lesser percentage of budget revenues than is

warranted by its’ size.

Program monies for Cadwalader total about $87,000. Most of this, about $64,000 is directed to Ellarslie. The park ranger program and special events program each receive about $10,000. Program monies are allocated from the Division of Culture and Division of Recreation budgets.

Table 3. Budgets for Cadwalader Park today (E. Timothy Marshall & Associates) and Appendix H