| Top | Master Plan Contents |

Chapter 2: History of the Park

INTRODUCTION

The evolution of Cadwalader Park mirrors the

growth of the City of Trenton in the last two

hundred years, but also reflects a significant

change in landscape style and attitude within the

region. The nineteenth-century country estate

that is now Cadwalader Park was profoundly

influenced by the ideas of Andrew Jackson

Downing, who set the definition of style for

American rural landscapes in the mid-1800s. The

firm of Frederick Law Olmsted and his sons was

responsible for much of the early design of the

park and its adjacent residential neighborhoods,

which were planned as a respite from the

crowded, industrial, urban setting of Trenton.

Cadwalader Park thrived as a well-loved and

much-used municipal park until after World War

II, when people began to travel more widely in

search of recreation. Over the next 50 years, the

park declined in a cycle of community misuse and

steadily decreasing municipal support.

The landscape history of Cadwalader Park shows

that the site has always been valued for its

proximity to the Delaware River, its gently rolling

terrain, large shade trees, and its views and vistas.

Above all, it has been revered as a pleasant

retreat, initially for private patrons and, subsequently,

for the citizens of Trenton. As its history

shows, the park also represents a significant legacy

of nineteenth/early twentieth century American

landscape design that is unique in the City of

Trenton.

Historical Document Search

An archival search was conducted, both to inform the master planning process and to provide the City with a reproducible archive of all relevant historical data pertaining to Cadwalader Park. The sources consulted were located in the City Hall archives, Cadwalader Park files, the Trentoniana Collection at the Trenton Free Public library, the New Jersey State Archives, the Archives of the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site, the Frederick Law Olmsted Papers and the Olmsted Associates Records at the Library of Congress, and the ollections of the Trenton Convention and Visitor Bureau. Copies of letters and textual material are listed in the appendices and technical memoranda. Original drawings have been copied into a reproducible format and will be a permanent archival resource for the City.

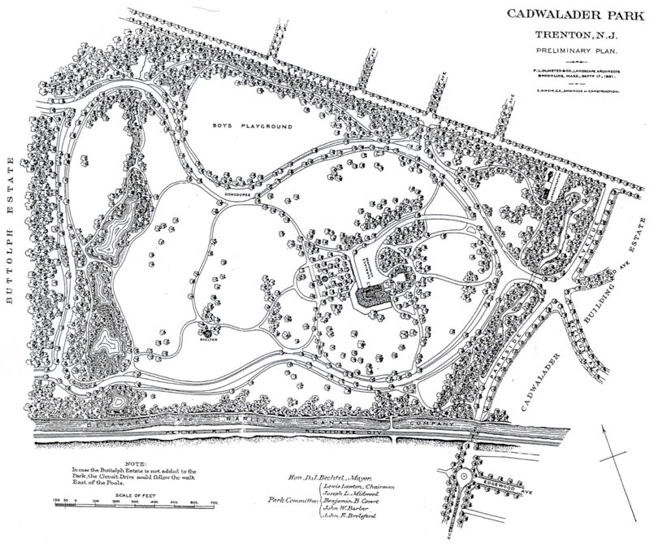

The 1891 Preliminary Plan (Figure 8) is the

only known surviving plan produced by the

Olmsted firm for Cadwalader Park during the

tenure of Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr. The

Olmsted office produced over 60 plans and

studies for the park between 1890 and 1911,

only three of which are known to survive

today. Two drawings done by the Olmsted

office in 1911, which were previously unknown

to the Cadwalader Park record, were

discovered by the Master Plan team during a

search of city archives. One drawing is a

layout and grading plan of the lower recreation

area, and the other a watercolor rendering

of the same area. (Figures 17 and 18). A

number of other landscape architectural

drawings, done in the 1920s and 1930s,

document the design history of the park

following the period of Olmsted Brothers

involvement. These technical drawings are

part of The Cadwalader Park archive.

Historical Chronology

In order to understand the development of the park landscape, the park history is divided into several major chronological periods. These are:

- Settlement/The Country Seat (1680–1743);

- Ellarslie/The Estate (1776–1888);

- Park Implementation (1888–1892);

- Cadwalader Park (1892–1911);

- Cadwalader Park (1912–1936); and

- Cadwalader Park (mid-century).

Each chronological period represents a significant

physical change in the park, also accompanied by

a shift in attitude toward the place. In general,

these changes mirror larger shifts that were taking

place within American society concurrent with the development of the park. The Country

Seat period, for instance, represents a time in

American settlement when wealthy individuals

sought retreat from the crowded and dirty

cities by building private park-like estates,

often as summer homes, on the rural edges of

urban areas. The period at the turn of the

century was a golden era for the building of

urban parks and park systems in the U.S.

Many of these parks were designed by the

same Olmsted Brothers firm which contributed

numerous designs for the construction of

Cadwalader Park.

| Top | Master Plan Contents |

SETTLEMENT/THE COUNTRY SEAT (1680–1743)

Situated on the eastern bank of the Delaware,

Trenton is located along the fall line, where

the Piedmont edge of the old Appalachian

range meets the coastal plain. At Trenton,

where the falls are located, the Delaware River

turns to the southwest and flows toward the

Delaware Bay. The falls are far more powerful

than they appear within the broad, shallow,

stony river.

In 1680, Mahlon Stacy, the Quaker immigrant

who is credited with the establishment of the

settlement at the falls, took advantage of the

natural water systems flowing from the east into

the Delaware River by constructing a grist mill at

the mouth of the Assunpink Creek. The site of

Stacy’s gristmill is considered to be the historic

center of Trenton. In 1714, William Trent bought

the Stacy holdings, upgraded the mill, and invested

capital in the community, which he called

Trent’s Town. Real estate advertisements and

travel accounts of the period confirm the agrarian

development of the countryside northwest of

Trenton by mid-century.

| Between 1742 and 1743, Dr. Thomas Cadwalader of Philadelphia advertised the sale of 700 acres of woodland located along the Assunpink. Cadwalader was a Philadelphian who was not only a large landowner but also became Trenton’s chief burgess, or mayor, shortly after he moved there in 1743.Trenton’s chief burgess, or mayor, shortly after he moved there in 1743. About this time, he set aside a tract northwest of the town for a “country seat.” Cadwalader’s holdings lay west of present-day Overbrook Avenue and extended north from the river toward, but not as far as, the old Scotch Road. Here, on his farmland, he constructed a residence called Greenwood, which became his permanent residence in 1746. |

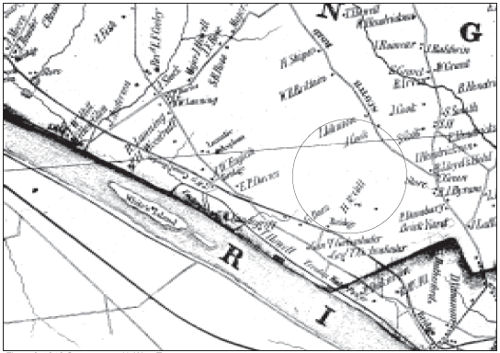

Figure 3. 1843 County Map with West Trenton Estates |

Prior to the Civil War, the most significant change to the old Cadwalader farmland was the construction of the canal feeder for the Delaware and Raritan Canal, which occurred between 1832 and 1834. This canal had been constructed across New Jersey, from Bordentown and Trenton on the Delaware River to New Brunswick on the Raritan River. The canal feeder, which extended for some 22 miles above the falls, provided the canal system with an appropriate supply of water from the Delaware River. Its route paralleled the river and crossed the old Cadwalader Farm. Although few bridges spanned the canal feeder, one bridge crossed the feeder just north of the Cadwalader family home, Greenwood, on the property that would become Ellarslie.

| Top | Master Plan Contents |

ELLARSLIE/THE ESTATE (1776–1888)

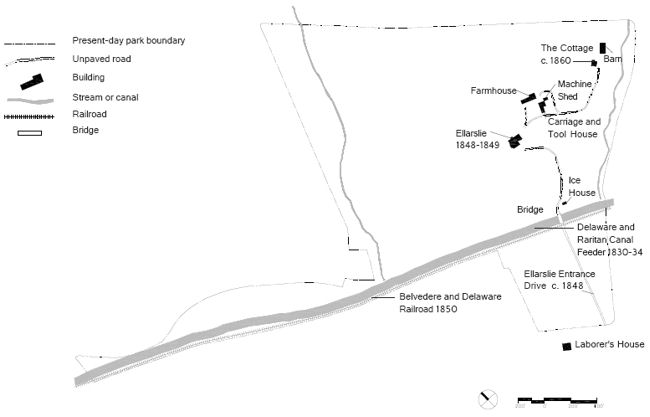

In 1776, the Cadwalader Farm consisted of 248 acres, which were subsequently partitioned to various family members. One parcel was eventually sold, in 1841, to Henry McCall, who built Ellarslie, the estate that would become the core of Cadwalader Park.

Figure 4. Ellarslie, early 1900s |

A county map of 1848 shows that other estates situated along State Street and the old River Road included the properties Glencairn, the Robert McCall estate, the Hermitage, and Henry McCall’s Ellarslie (Figure 4). All but the Hermitagewere designed between 1847 and 1850 by the architect John Notman of Philadelphia. Most of these residences were enhanced by landscapes featuring curvilinear drives and naturalistic styles of planting, in the “picturesque aesthetic” advocated by both Andrew Jackson Downing and Notman. |

Downing described Notman as one of two “successful American architects,” (Andrew Jackson Davis being the other), capable of understanding “rural architecture.” The two men each worked on the design of the New Jersey State Lunatic Asylum, which was located just beyond the western boundary of Henry McCall’s property. Notman began his design of the building around 1845 and continued his work there until 1848. Downing apparently became involved in this project at about that time, and prepared plans for the completion of the grounds.

Ellarslie

Although no images of Ellarslie or the grounds

from the time of the McCalls’ ownership are

known to exist, statements made about the

property indicate that the site was distinguished

by at least three character-defining elements: its

architecture and clusters of buildings, its specimen

trees, and its entry drive. The first of these

elements concerned both the visual appearance

and the arrangement of structures on the southwest-

facing slope. The Italianate villa, described as

a “handsome modern, substantially built stone

edifice, rough cast, with broad piazzas,” was the

centerpiece of the arrangement (Figure 4).

Notman’s placement of the “piazzas” on the west

and south sides of the house suggests that

Ellarslie’s architecture was designed to take

advantage of broad panoramic views down the

open slopes toward the Delaware River. The

main house was supported by groups of outbuildings,

including two pumps, an ice house,

stables for four horses and four carriages, a

gardener’s house, and a greenhouse. A farmer’s

(tenant) house and a barn may also have been

located on the property.

| Many of the fine old trees extant in the twentieth century were likely planted in the nineteenth century by McCall’s landscape gardener. Given that the estate’s entry drive was noted for the “growths of heavy shade trees” bordering its graceful curves, it is likely that the landscape gardener carefully sited the trees with respect to the topography and to the locations of the residence, outbuildings and curvilinear drive. By 1860, the grounds had been embellished with additional plants, such as pear and other fruit trees, as well as evergreen and ornamental trees. |

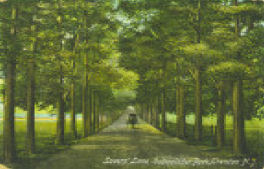

Figure 5. Lovers' Lane |

The entry drive lay in a straight alignment from its

beginning at the Old River Road (now West

State Street), crossing the feeder canal in a direct

line and winding its way up to Ellarslie. The treelined

drive from the road to the bridge subsequently

became known as Lovers’ Lane by the

young couples who frequently strolled there

under the canopy of American beeches (Figure

5).

By 1881, when Henry McCall sold Ellarslie to

New York broker George W. Farlee, the estate

was noted for its “oaks, maples, pines, beeches,

evergreen and cypress trees.” Farlee used Ellarslie

as a summer villa and farm, with some of the land

set aside to raise Jersey cattle. The most significant

change to the property occurred shortly

after Farlee’s purchase when he subdivided a

portion of the tract into small lots for the development

of a residential neighborhood to the

north of Ellarslie that was later called Hillcrest. By

1888, Farlee had put the remaining 80 acres of

Ellarslie up for sale. At the time of its acquisition

by the city, the Ellarslie estate consisted of a main house, a farm house, frame cottage, a small brick

house, barn, carriage and tool house, machine

shed and icehouse (Figure 6: Ellarslie/The

Estate).

Figure 6. Ellarslie / The Ellarslie Estate 1776-1888

| Top | Master Plan Contents |

FREDERICK LAW OLMSTED AND THE OLMSTED FIRM

Cadwalader Park and Olmsted’s National Career

By the time he began to design Cadwalader Park

in 1890, Frederick Law Olmsted had been

planning parks in the nation’s leading cities for

over thirty years. In 1858, he and his partner

Calvert Vaux had won the design competition for

Central Park in New York, the best of thirty-two

entrants. Over the next fifteen years Olmsted

and Vaux went on to design Prospect Park and

Fort Greene Park in Brooklyn, Washington and

Jackson parks in Chicago, and the Buffalo park

system. Then, working on his own, Olmsted

planned the park at Mount Royal in Montreal and

Belle Isle in Detroit. In 1884, his stepson, John C.

Olmsted, became his partner and the two men

collaborated closely in planning the extensive

system of Boston parks known as the “Emerald

Necklace.” Two years before they began work on

Cadwalader Park, the Olmsteds started planning

the park system of Rochester, NY; and in 1891

they initiated the design of the park system of

Louisville.

Accordingly, both Frederick Law Olmsted and John C. Olmsted had extensive professional experience to draw from while working in Trenton. No other landscape architects in the country had anything like their experience and reputation.

Cadwalader Park and Olmsted Firm’s Park Design Work in New Jersey

Cadwalader Park is notable as the only park in

New Jersey designed by Frederick Law Olmsted,

Sr. Olmsted’s work on Cadwalader Park took

place during the years 1890 to 1892. The

Olmsted firm also participated in planning

residential subdivisions on Cadwalader family

property adjacent to the park. One development,

along East State Street, was called

Cadwalader Place, while the other area, across

Parkside Avenue from the new park entrance,

was called Cadwalader Heights. The Olmsted

firm advised on both sites in 1890- 92, and

returned to plan Cadwalader Heights more fully

during 1905-11. The major period of the

Olmsted firm’s park work in New Jersey began in

1895, the year of his retirement. Over the next

forty years the firm designed some twenty-eight

parks, parkways and scenic reservations for the

Essex County park system, as well as a number of

parks and parkways in Union and Passaic counties.

The Olmsted firm also did additional park

planning in Trenton: in 1907, Frederick Law

Olmsted, Jr., submitted a detailed proposal to

create a linear recreational area along Assunpink

Creek and, in the same year, the firm drew up a

plan for a “stadium” on the site of the reservoir at

Pennington and Prospect Streets. Cadwalader

Park, therefore, marked the beginning of a highly

significant period of park planning by the Olmsted

firm in New Jersey. Trenton is one of a small

group of American cities that benefited from

park-planning by all three Olmsteds who were

principals in the firm: Frederick Law Olmsted, his

stepson and partner John C. Olmsted, and his

son, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr.

Surviving Correspondence and Plans

In designing his parks, Olmsted often wrote

extensive reports explaining his design intent and,

with his staff, drew up a series of plans at every

stage of construction. However, very few of the

firm’s more than sixty plans for Cadwalader Park

have survived. The crucial plan, the lithograph of

September 1891, is readily available, but none of

the working plans leading up to that proposal,

and only one of the planting and construction

plans generated during the years immediately

following, are known to exist. This was a plan for

the Parkside Avenue tunnel under the Delaware& Raritan Canal and railroad that the Olmsted

firm commissioned from the Boston architectural

firm Walker & Best (See: Cadwalader Park

Archive) in 1892. Many of the other plans

apparently survived in the vaults of the Olmsted

firm in Brookline, Massachusetts, until 1968. In that year, the City of Trenton requested copies

of plans for anticipated work on Cadwalader

Park. The Olmsted firm sent the originals instead,

and they are believed to have been lost in the fire

at the Armory in 1975. In Trenton, the only plans

that appear to have survived were done during a

much later work effort. These are plan no. 61 of

January 12, 1911 showing grading and paths for

the section of Cadwalader Park below the canal,

bounded by Parkside Avenue, Riverside Avenue,

and what is now Lenape Avenue; and plan no. 66

of January 14, 1911, a colored preliminary plan of

recreational facilities, plantings, and walks for the

same area of the park (Figures 17 & 18). These

plans, discovered by the master planning team in

the city’s plan files, had been lost for over thirty

years.

Olmsted did not write an extensive report about Cadwalader Park, apparently because he expected that it was going to be considerably enlarged. He anticipated that the city would acquire the additional land along the Delaware River needed for a river drive between the State House and the park. In fact, he was asked to draw up a plan for the river drive, and did so in early 1892. There was also agitation in the city in those years for purchase of the full one hundred acres of the Buttolph property that lay between the original park lands and the State Hospital for the Insane, and Olmsted fully expected to expand the park plan of 1891 to include some or all of that land. Anticipating these changes, he made no final written description of the plan.

Extensive correspondence concerning the park

has survived, nonetheless, particularly in the

letterpress books where the Olmsted firm

recorded outgoing letters. In all, 85 pieces of

correspondence survive from the time of the

firm’s involvement with the park between 1890

and 1911. The subjects they address indicate

Olmsted’s ongoing concern with expansion of

the park and access to it. The categories with the

most letters have to do with acquisition of the

Buttolph property, the River Drive project, and

construction of the Parkside Avenue tunnel

under the Delaware and Raritan canal and

railroad that would provide safe passage to the

new, main park entrance and make possible more

convenient access to the territory north of the

park. The feature within the park itself that

receives the most attention in the letters of the

firm is the stone entrance bridge and arch at

Parkside Avenue. The most significant statements

on 30 different subjects have been transcribed

and are arranged by subject in the “Olmsted Firm

Documentary Record for Cadwalader Park, 1890

– 1911” prepared by the master plan team. In

addition, all of the plant orders to nursery firms,

drawn up by the firm in the fall of 1891 and

spring of 1892, have survived, giving the species,

numbers, and size of some 27,000 trees, shrubs,

and groundcover plants that were planted in the

park at that time based on the plans of the

Olmsted firm and directed by members of its staff (see Appendices).

| Top | Master Plan Contents |

PARK IMPLEMENTATION (1888– 1892)

Early Stages of Park Planning, 1888– 1891

In 1888, the City of Trenton acquired most of the present site of Cadwalader Park, some 80 acres, from George W. Farlee for $50,000. Ten acres of the land was south of the canal, and the park included another ten acres in a narrow strip two-thirds of a mile long running along the Delaware River. The intent was to secure additional land and use this strip for a drive leading to the park. This concept had been proposed by Russell Thayer, Superintendent of Fairmount Park in Philadelphia, and was approved by Trenton’s mayor and common council during 1888. After the property transferred to the city on May 22, 1888, 5,000 people came out on the following weekend to the old estate to enjoy the grounds and the open spaces. Park reports also noted that the first of many band concerts was held in July 1888 from the “piazza” of Ellarslie.

|

The Trenton baker, caterer, and civic leader

Edmund Hill was a member of the Common

Council’s Park Committee (1888–1890), and

had played a leading role in the park movement

from its beginning. Once the Farlee land was

acquired, he and other members of the committee

began to plan new drives for the park.

They also engaged the Philadelphia engineer

George N. Bell to make a topographical map

of the park. This was completed in July 1889,

and Hill then proceeded to sketch out a plan,

which has not survived. He gave this plan to

Bell in September, and the next month Bell

presented a preliminary plan, of which Hill

said “he had adopted my main features,

changing some for the better and some for the

worse.” Hill proposed some changes in Bell’s

plan, but was dissatisfied with the revised plan

that Bell presented. Accordingly, Hill continued

to work on his own plan. In February 1890,

he arranged for the sanitary engineer George E.

Waring, Jr., to visit the park and examine his plan.

Waring had been the drainage engineer for

Central Park during its first years of construction,

when Olmsted was architect-in-chief of the park,

and had collaborated with Olmsted on several

projects over the ensuing thirty years, including

the Stanford University campus. It is possible that

Waring recommended that Hill employ Olmsted

to design Cadwalader Park since, two weeks after

Waring’s visit, the Park Committee decided to

seek Olmsted’s counsel. On March 12, 1890, Hill

wrote Olmsted to learn his terms for laying out

the park. On March 25, Hill offered to pay

Olmsted $150 to examine both the park site and

the Cadwalader family lands that Hill was in

charge of developing for residences. Olmsted

promptly offered to visit four days later, but

other commitments forced Hill to postpone the

visit until April 11, 1890. The visit was satisfactory,

and, on May 2, Hill wrote Olmsted informing him that the Park Committee had selected

him to prepare plans for the park.

Figure 8. 1891 Preliminary Plan of Cadwalader Park Frederick Law Olmsted Office

By September 1890, Olmsted had completed a preliminary plan, which John C. Olmsted presented to the Park Committee on September 13. On that same day, the common council approved the Olmsted plan and authorized the Park Committee to negotiate for the land.

The Olmsted Plan of September 1891

The “Preliminary Plan” of 1891 represents the final version of Frederick Law Olmsted’s design for Cadwalader Park (Figure 8). The plan has numerous elements that are characteristic of an Olmsted park. Chief among these are an arrangement that makes full use of the landscape qualities of the site, and a coherent system of walks and drives by which the scenery can be enjoyed in all kinds of weather (Figures 9 and 11).

Formal Area—Refectory and Concert Grove A central element of the plan is the Ellarslie

mansion, which Olmsted proposed to retain and

to devote to park purposes. He wished to turn it

into a “refectory,” that is, a restaurant for park

visitors. In addition to the space inside the

mansion, he proposed to construct a vinecovered

trellis on two sides of the building, 220

feet long and 40 feet wide. This feature closely

resembles the refectory in Franklin Park in

Boston that he was planning at the same time,

which included a similar outdoor dining

space. Cadwalader Park was the only other

park where he planned such a trellis structure.

Access to the refectory was also carefully

planned. Olmsted proposed to demolish the

old approach road that had run up Lovers’

Lane and across the canal. Instead, he integrated |

Figure 9. Scene at Cadwalader Park illustrates open quality beneath tree canopy typical of early park |

The concourse provided a spacious gathering place for the carriages of those using the refectory: it also overlooked the music stand in the adjoining concert grove. By this means, Olmsted introduced a feature that he and Calvert Vaux had first used in Prospect Park in the 1860s—a concert area designed for both pedestrians and people in carriages. The refectory and concert areas, combined with the series of wide paths leading to them, provided a well planned section of the park that was suited for the gathering of large crowds in a place where they would not injure or intrude on the landscape of the rest of the park.

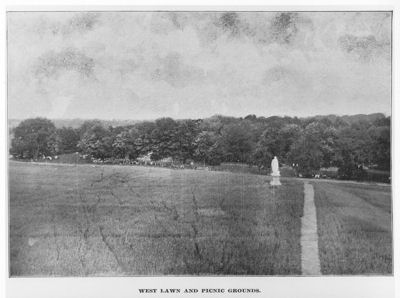

Pastoral Landscape

| West of Ellarslie and the concert grove stretched the most distinctive landscape area of the park, the open meadow that extended unbroken to the shores of the pools in the western ravine, over three hundred yards away, and ran an equal distance from the carriage concourse on the north to the circuit drive on the south (Figure 10). Within the walks encircling this open space, deciduous shade trees were to be distributed in open groves or stand as single specimens. This was the kind of landscape Olmsted always included in his parks, a landscape that he believed had a special restorative quality, a unique ability to counteract the artificiality of the city and provide relaxation from the stress of urban life in the industrial age. Part of the quality of this scenery was its invitingness, its “hospitality,” which was enhanced by the graceful contouring of the terrain, the long views, and the sense of limitless space. The scattered trees continually opened up new vistas as the visitor passed through the meadow, either on the close-cut turf or on the few meandering paths. The trees also obscured the boundary plantings, increasing the indefinite edge of the space. This meadow was to be used by all park visitors, and not monopolized by any particular group. In this way, people of all ages could share it, resting, picnicking, and playing informal games. |

Figure 10. Open meadow following the design by Olmsted firm, with single grove of trees for scale definition |

It is difficult to estimate the number of extensive

vistas that would have been available from the

top of the meadow before trees grew up on land

to the south and west, but presumably there

were views of the Delaware River from the

concourse at the north end of the meadow, and

from the Shelter at the southern end of the ridge.

Both of these points were reachable by paths, as

was always the case for the high vista-points in

Olmsted parks.

To achieve the desired feeling of openness,

Olmsted used deciduous shade trees almost

exclusively, as can be seen in the historic photographs

of such famous meadow areas as the

Sheep Meadow in Central Park and the Long

Meadow in Prospect Park. In the meadow section

of Cadwalader Park today there are too many

trees, so that both the intended openness and

the chance to experience the unfolding landscape

of Olmsted’s original design have been lost. The

large number of coniferous evergreens, which

close up the space in all seasons, are a particular

problem. The few relevant historic photographs

indicate the contrast between Olmsted’s design

intent and current conditions, as does the

documentary record. In the Olmsted firm’s list for

the 27,000 trees to be planted in the interior of

the park in the spring of 1892, there are no

evergreen conifers among the 48 species of trees

listed. In fact, the firm did not order a single

evergreen tree at any point during the planning

and construction of the park, either for the

boundary plantings or for the interior.

Figure 11. Circuit Drive in Cadwalader Park - early years |

Initial improvements simply added park features, such as benches, tables, and a temporary bandstand, or demolished agrarian estate features, such as the fences. A prairie dog village was laid out and the Ellarslie residence was converted into space for a natural history museum and a refectory. Citizens began to donate small animals and birds to the park, thus establishing a menagerie. The old stable and other outbuildings were converted to accommodate this “zoological garden” and the variety of animals grew to include larger animals such as deer, monkeys, and a black bear cub, brought to the park by Edmund Hill (Figure 7). |

It should also be noted that the spaciousness of

the meadow has been significantly compromised

by the “dogleg” road that was added in the early

twentieth century, cutting through the terrain

that was intended to rise gradually westward

from the concert grove. Where Olmsted intended

to have a narrow band of deciduous

trees, the road has a visually impenetrable border

of Norway spruces.

Circulation System

In Olmsted’s plan, the key element of the circulation

system is the circuit drive that encloses the

principal landscape section of the park—Ellarslie

and its surrounding lawns and groves, the concert

grove, the meadow, and the stream and pools

of the western ravine (Figure 11). Inside that

drive is a single carriage drive, for access to

Ellarslie and the concert grove, and a series of

paths arranged for access and enjoyment. The

drives and walks are constantly curving, and

have no straight sections. By this method, new

landscape is constantly revealed as one moves

through it. Only in the concert grove area are

there any straight paths, and these are in

keeping with the formality of the area and the

need for sight lines toward the band stand. As

in Olmsted’s other parks, the paths were to be

well constructed and wide; those leading from

the Parkside Avenue entrance to Ellarslie

appear on the plan to be twenty feet wide,

while most of the rest of the paths in the park

show as fifteen feet wide. Only in the ravines

were there to be narrower paths—ten feet

wide in the eastern ravine and a few apparently

as narrow as six feet near the pools in

the western ravine.

Figure 12. West meadow was originally open, with a vista to the playground area |

For nearly the entire distance of the circuit drive,

pedestrian paths run close to it on both sides.

This made it possible to make a full circuit on

foot of the heart of the park with minimal

crossing of carriage traffic, while at the same time

one could walk along the outside of each major

section of the drive without crossing it. The drive

as originally planned would not have been visible |

Boundary Areas

Two significant elements were placed outside the

drive: the Boys Playground and the administration

buildings. The playground was sited so that it

would appear as an open meadow partially

obscured by the densely planted trees north of

the concourse, thus separating active sports from

the scenic sections of the park while adding to

the sense of space of the park as a whole

(Figure 12). The administration buildings were

to be placed next to Stuyvesant Avenue behind

a thick planting of trees.

On the very edge, Olmsted planned an

impervious barrier of trees that would screen

the park from the adjacent neighborhoods, as

he did in the other parks he designed. No

houses on adjoining streets were to be visible,

nor were householders to have a view into the

park; it was to be a separate and very different

world. The firm’s nursery orders and park

reports show that, for the border on the north,

8,500 trees and 4,830 shrubs were purchased

and planted, while for the border

plantation along the canal 14,110 “small

trees and wild shrubbery” were installed. The

dense boundary planting along the canal was

designed to keep park visitors from having

access to the canal, which was not considered a

recreational facility at the time, but was a heavily

used commercial and industrial facility. At the

time, screening and separating this industrial use

from the park was appropriate.

Further separating the park from the canal,

Olmsted proposed to demolish the old entrance

drive to Ellarslie. The old bridge crossing the canal

at that point was to remain, but at its northern

end, paths were to lead only down to the canal

towpath. Between the bridge and the southern

circuit drive, there appears only a deep, dense

grove of trees and thick plantings of thorny

shrubs and climbers.

Playgrounds and Team Sports Facilities

Another aspect of the firm’s planning in the early

1890s was the provision for a playground south

of the canal, in an area that included ten acres

purchased from George Farlee in 1888, as well as

the triangle of land between Lovers’ Lane and

Parkside Avenue that the city did not formally

acquire from the Cadwalader family until 1910. In

January 1892, the firm provided a plan for this

section, called “Cadwalader Playgrounds,” or

“Cadwalader Common.” Other than the “Boys”

Playground, it is unlikely that the plan provided

space for any particular team sports. However,

by the end of the year, the “common” had

been “improved by laying out a baseball

diamond and cricket field.” The Olmsted plan

included a sidewalk and rows of shade trees

along Parkside Avenue and the northern

border (i.e., along Lenape Avenue). As described

by the Olmsted firm, “At either end of

the Playgrounds these two promenades are

connected by cross walks, which are without

trees because trees would interrupt the view of

the Delaware River from Cadwalader Park.”

Lovers’ Lane, “raised upon an ugly embankment”

that cut the upper playground in two, was

to be removed as soon as the tunnel under the

railroad was constructed and the old park

entrance could be abandoned.

Eastern Ravine

The ravine just west of Parkside Avenue, where

Olmsted sited the new main entrance to the

park, received a large amount of attention during

the early years of the park. This was one of the

areas that Olmsted urged the city to acquire in

order to fill out the park boundaries beyond the property acquired from George Farlee in 1888.

John L. Cadwalader and his family gave the seven acre

ravine area to the city in the fall of 1891.

The development of this section was always

intertwined with the Cadwalader family’s development

of Cadwalader Heights on the other side

of Parkside Avenue. Edmund C. Hill was in charge

of the development. In 1890, he hired the

Olmsted firm to draw up the plans for this area

and to review plans for the Cadwalader Estate

residential development south of the canal

bounded by Parkside, Overbrook, Edgewood,

and Berkeley avenues. The hillside on the western

edge of Cadwalader Heights overlooked the park,

and the two streets planned by the Olmsted firm

at that side of the development, Rutherford

Avenue and Bellvue Avenue, were to meet at

Parkside Avenue directly across from the new

main entrance to the park. The Cadwalader

family shared some of the expense of constructing

Parkside Avenue north of the canal with the

city and contributed additional land to facilitate

construction of the tunnel under the railroad and

canal. Edmund Hill even loaned his workmen to

help prepare the ravine for park use and to

construct the drives at that end of the park.

In the plan of 1891, one finds two major elements

of the eastern ravine. One is the brook

running the length of the ravine, which had to be

redirected for part of its course, with dense

plantings on both banks that also served as |

Figure 13. Parkside Avenue entrance bridge, c. 190

|

Olmsted had not included such a feature in a

park since the planning of upper Central Park in

the early 1860s. In that area, he and Calvert Vaux

had installed three such arches, each carrying a

carriage drive over a path and stream—Springbanks Arch, Huddlestone Arch, and the

Glen Span. These Central Park arches and the

single bridge in the Cadwalader Park ravine

are the only arches with a stream and walk

running through them that Olmsted included

in any of his parks.

Western Ravine

In the broader wooded valley at the west end of

the park, Olmsted planned a series of pools that

was reminiscent of the Pool and Loch of upper

Central Park, or of the water feature that he and

Vaux had created along the Long Meadow and in

the Ravine area of Prospect Park. The Preliminary

Plan of 1891 shows most of the Ravine taken up

by five naturalistic pools (two of them probably

the quarry and sandpit that were providing fill

material for roads and paths) with a connecting

stream. The three lower pools are shown

surrounded with dense vegetation, while the

borders of the two upper pools are somewhat

more open and more visible from the adjoining

meadow areas. These upper pools have four

beach areas where the nearby path expands to

form a shallow wading area. Olmsted and Vaux

had included such beaches in the upper pool in

Prospect Park, and at this time Olmsted was

constructing similar ones along the Muddy River

in the Boston Emerald Necklace. These water

features were an important part of the park and

its landscape as Olmsted envisioned it.

When it was proposed, in 1895, to reserve part of this area for a deer paddock, the firm replied that a temporary enclosure might be provided in the northwest corner of the park, but stated that “when the pools shall have been formed here, it will be found essential, we believe, to permit the public to have the privilege of walking near the Buttolph property on the western edge of the ravine must be acquired to give the park the breadth it needed. Accordingly, he showed the western section of the circuit drive on land that was not yet part of the park, running approximately where Cadwalader Drive is today. He appended a note to the plan, saying, “In case the Buttolph Estate is not added to the Park, the Circuit Drive could follow the walk East of the Pools.” This was, finally, where the drive was constructed. The Buttolph land was never acquired, and this had a major impact on the formation of the pools, their relation to the meadow, and the coherence of the circuit drive itself. In addition, it meant that the dense boundary planting at the western edge of the park was never created. Furthermore, the northwest corner of the park, with the ball field and the upper pool, was presumably not developed until after acquisition of that land from the state in 1926.

Construction of the Park, 1890–1892

Construction of the park with Olmsted’s guidance began soon after he received the commission on May 2, 1890. He and John C. Olmsted were at the park as soon as May 21, and offered suggestions that were soon ncorporated into working drawings. On May 31, for instance, the park engineer E.G. Weir completed a new “detail engineer map” that incorporated a number of Olmsted’s suggestions and was, according to Edmund Hill, “more practical, has truer grades, reduces excavation, and is far better” than the previous plan drawn up by a local engineer. In mid-September, John C. Olmsted came to Trenton to present the first preliminary plan, which the common council promptly adopted. During the years of park construction when Olmsted and his firm were closely involved in the process, work on the circulation system progressed rapidly.

Circulation System

Between January and March 1891, the firm

completed plans for the park roads and staked

out their route on the ground. During March,

construction of the road from the main park

entrance to the Hillcrest Avenue entrance began,

as well as some of the other drives, and during

the next four months, Olmsted supplied plans for

the eastern ravine and its entrance bridge.

For the permanent carriage drives, the Olmsted

firm used a system of “macadamized” roads

according to the “Telford” system. These were

stone roads ten inches deep that were rolled by

heavy rollers at appropriate stages of construction

and topped with two inches of fine crushed

stone. The macadamized roads were thirty feet

wide and had cobble paved gutters where the

grade was greater than 21/2 percent. In order to

secure adequate drainage, they were underlain by

a system of tiles and catch basins. By the end of

the Olmsted firm’s oversight of construction in

1892, one mile of this macadamized drive

had been constructed, which was the full

length of drive possible without acquisition of

the Buttolph property. In addition, the Olmsted

firm agreed to construction of a temporary

drive connecting the north and south ends of

the circuit drive on the west side, since the

Buttolph property needed to carry the drive

around the west side of the western ravine had

not yet been acquired. Construction of this

drive, completing the circuit drive, occurred in

1892. Eventually this drive became the permanent

western end of the circuit drive. Macadamizing

of the circuit drive was completed in 1893.

As for the more than two miles of pedestrian paths in Olmsted’s plan, the records do not indicate that any of them was constructed with the course, width, grade and engineering features that he intended. None of the paths in the park today matches the plan of 1891. The park commission’s reports record construction of nearly one mile of paths between 1892 and 1895, but nothing more is known about them.

Plantings

Supervision of planting in the park got underway

in October 1891, during a visit of Warren

Manning, the chief plantsman for the Olmsted

firm. Manning arrived with lists and estimates of

the cost of installing border plantings along

Stuyvesant Avenue and the canal, as well as trees

to plant in the park as individual or in open

groupings, during the fall. As a result of the visit,

Lewis Lawton, chairman of the park commission,

authorized expenditure of $700.00 for this

purpose. The firm then ordered some 25,000

plants to make an impenetrable border along

Stuyvesant Avenue and the Delaware &

Raritan Canal. When planting resumed in the

spring of 1892, the last season of planting

that the Olmsted firm directed, they received

authorization to purchase 500 additional trees,

eight to ten feet high, for “general planting in the

interior portions of the Park.” All of the trees of

this size that they ordered were large-growing

shade trees, with maples (114), elms (91), and

beeches (47) being the most numerous species;

none were coniferous or evergreen. As the firm

explained, “some of them are intended to give

shade along the lines of road already graded, and

others to furnish the bare, open field west of the

Concourse. These last will, of course, be so

disposed as not to block out the view.”

One major alteration to the Olmsted plan came in 1893, the year after their direction of construction ended. The newly formed Park Commission, in its first year of existence, noted that, while many small trees had been set out, the circuit drive was “in many parts exposed to the sun.”

Figure 14. 1898 photo illustrates evenly spaced trees along the park road, contrary to Olmsted plan |

They, therefore, planted 150 larger (12 to 15 |

This seems to have established a tradition of street tree spacing along the drives that was the basis for the planting of many of the trees that line the drives today. Between 1894 and 1898 the new Park Commission planted an additional 200 to 450 trees in the park, although the species and areas of planting are not documented.

| Top | Master Plan Contents |

CADWALADER PARK (1892–1911)

Olmsted Involvement 1892–1910

The year 1892 saw significant changes in the

management of Cadwalader Park. A new

mayor was elected who represented groups

opposed to further major expenditure on parks.

This coincided with establishment by the state

legislature of a Park Commission appointed by the mayor (up to this point the park had been

overseen by a park committee of the common

council and selected by it). The new Park Commission

first met on April 26, 1892 (Olmsted’s

seventieth birthday) and there is no record of any

correspondence between them and the Olmsted

firm for the next three years. They apparently did

not attempt to retain the services of the Olmsted

firm.

The spring of 1892 marked the last stage of the Olmsted firm’s direct influence on the planning of construction of Cadwalader Park above the canal, except for the redesigning of the entrance path near the Parkside Avenue tunnel in 1910 (Figure 15). The only involvement of the Olmsted firm between the spring of 1892 and its resumption of work on Cadwalader Park in 1910 was their response to two queries concerning the placing of new features in the park. The first came from the Park Commission in March 1895, a request for a suitable site for an enclosure for some deer that had been presented to the commission. The firm replied that “the Park is so small relatively to the number of people who will use it, especially upon holidays, that no considerable area can be set apart exclusively for a deer paddock.” |

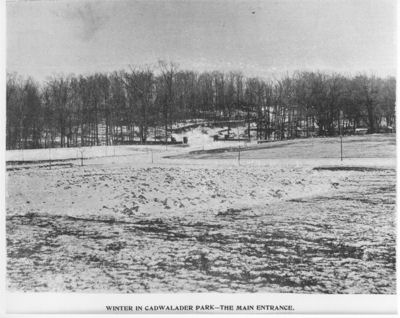

Figure 15. Parkside Avenue Tunnel |

Park Projects, 1892–1911

With the Olmsted firm no longer in the picture,

the Park Commission and city council continued

to add monuments, buildings and facilities to the

park and accept donations of animals from local

citizens. The statue of George Washington

crossing the Delaware that had been exhibited at

the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition was

dedicated in 1892. Cages were built to

accommodate the park’s growing population

of animals, including a cage for the existing

bear pit. A fifty-foot tall rustic observatory was

sited on the knoll above the statue of Washington.

Cadwalader Park was officially dedicated on

May 1, 1902, but improvements continued to

be made well into the twentieth century. In

1897, a skating pond and refreshment

pavilion was created within the lower recreation

area below the canal. The pond was

filled in by 1906 and tennis courts were sited

on the fill. A Gardener’s Cottage was located

above the canal and entry pillars were constructed

at Parkside Avenue. Around 1902, a

large pavilion, the “Grand Lodge,” was sited near

the canal. Stuyvesant Avenue received a rustic

style entrance gate in 1907. The following year,

the Roebling statue was erected, followed by the

Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Battle Monument

in 1909. Lawn bowling greens and walks from the

northwest side of the Parkside Avenue tunnel

were constructed in 1910 (Figure 16: Building the

Park 1889-1911).

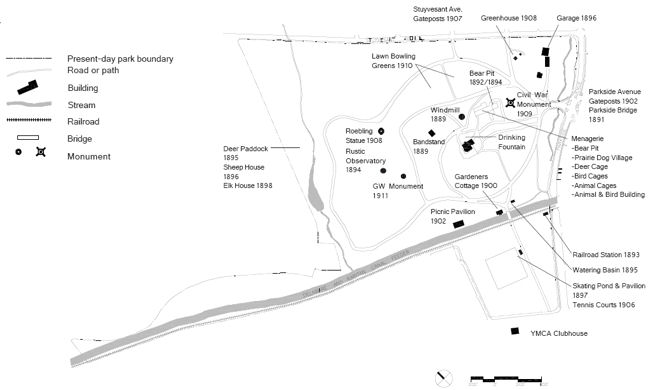

Figure 16. Building the Park 1889-1911

Olmsted Involvement 1910–1911

The spring of 1892 marked the last stage of the Olmsted firm’s direct influence on the planning of construction of Cadwalader Park above the canal, except for the redesigning of the entrance path near the Parkside Avenue tunnel in 1910 (Figure 15). The only involvement of the Olmsted firm between the spring of 1892 and its resumption of work on Cadwalader Park in 1910 was their response to two queries concerning the placing of new features in the park. The first came from the Park Commission in March 1895, a request for a suitable site for an enclosure for some deer that had been presented to the commission. The firm replied that “the Park is so small relatively to the number of people who will use it, especially upon holidays, that no considerable area can be set apart exclusively for a deer paddock.” The firm did, however, suggest three possible sites for a temporary enclosure, none of which was in the place eventually chosen by the Park Commission for what became a permanent deer paddock.

In May 1910, Edmund C. Hill inaugurated the last

stage of the Olmsted firm’s work on Cadwalader

Park when he sent a map of the park between

the canal and the Delaware water-power

canal, with the request for a plan for its

development. The plan was to be paid for by

the Cadwalader Estate, which was in the

process of selling to the city the triangle of land between Parkside Avenue, West State Street, and Lovers’ Lane (an expansion of the |

Figure 17. 1911 Design for Lower Recreation Area, Olmsted Brothers Office |

Figure 18. 1911 Design for Lower Recreation Area, Olmsted Brothers Office

As early as October, the firm provided a preliminary plan that proposed the addition of some tennis courts and construction of a wading pool for children. In its grading plan of January 1911, the firm designed graceful circuit paths for the two sections of the area, above and below West State Street, and created a much less awkward grading of the shoulders of Lovers’ Lane.The sides of the southern section were mounded up to make long berms rising to four feet in height that were to be densely planted with trees and shrubs. The last surviving preliminary plan, of January 14, 1911, shows twelve tennis courts next to the canal and a ballfield west of Lovers Lane. In the section south of State Street, there is a central lawn with space for a future running track and a hundred-foot-long pergola at its south end, connecting what are probably two small toilet and locker-room structures.

Construction of the Parkside Avenue tunnel

under the railroad and canal was going on at this

time, and Parkside Avenue was being regraded |

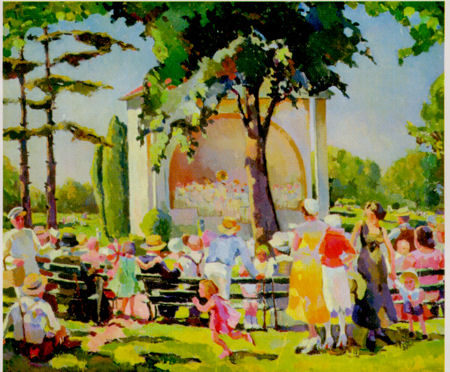

Figure 19. 1931 painting of the bandshell at the height of Cadwalader Park’s popularity |

Existing records, the diary of Edmund Hill, and known newspaper accounts give no indication that the firm played any further official role in the design or upkeep of Cadwalader Park. Despite that fact, the basic outline of Frederick Law Olmsted’s concept and his layout for the park and its major use zones remains today.

| Top | Master Plan Contents |

CADWALADER PARK (1912–1936)

Ten years after its dedication, Cadwalader was a popular community park, with parades, reunions,

celebrations and visitors who loved strolling along

its paths . The park advertised itself with displays

of annuals beds spelling “CADWALADER PARK”

along the canal embankment. The annuals were

grown in the park greenhouse, constructed

around 1908. A postcard of this period also

shows a gardener’s cottage near the canal, one of

several structures that were built at this time.

Two barns were built in the deer paddock

around 1913, which are still being used today for

the park deer. The menagerie buildings, which

had been adapted from the old Ellarslie carriage

house and stables, were replaced by a new

monkey house, animal shed, and aviary; and the

nearby bear cage was enlarged. A comfort station

and a ranger station, constructed near Ellarslie

around 1913, and the field house for the recreation

area, constructed near Lovers’ Lane,

increased the amenities for park visitors. A new

bandshell was built in the concert grove in 1913

(Figure 20: Cadwalader Park 1912-1936).

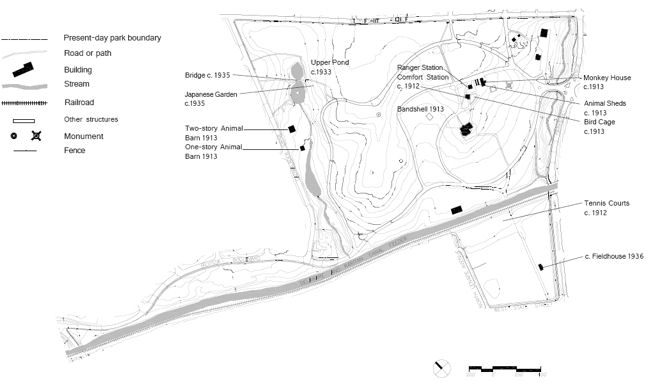

Figure 20. Cadwalader Park 1912-1936

The deciduous trees selected by the Olmsted firm and planted along the drives and park boundaries in 1892, began to reach mature heights and develop full canopies at this time. Their striking form and mass were complemented by the older Ellarslie trees, making the arrangement of trees an important character-defining element of the park. Natural events, however, were taking a toll on the park trees. Chestnut blight in the first decades of the century, Dutch elm disease in mid-century, and Hurricane Carol in 1954 damaged many of the older trees, planted during the estate and Olmsted eras. A significant change to park access occurred during this period. Sometime prior to 1925, the old bridge over the canal feeder was removed. Lovers’ Lane, the original entrance to the estate, now ended at the canal, and the Parkside Avenue entrance bridge clearly became the main entrance to the park.

WPA Projects

The Works Progress Administration of the New Deal era brought an influx of public spending, and, in retrospect, some long-term changes with consequences for West Trenton and Cadwalader Park. Most significant for the park was the conversion of the lower rooms and veranda of the Ellarslie mansion into a monkey house for the park menagerie. Unemployment relief funds, provided between 1931 and 1936, paid for building the upper pond in the northwest corner of the park, a tree survey, and general grounds improvements.

One of the larger WPA projects in Trenton was

the filling of the Delaware and Raritan Canal,

from Lock 2, to its junction with the feeder

canal that passes through Cadwalader Park.

This action ended all possible navigation

through the city, and rendered the canal feeder

obsolete as a shipping channel, although the

feeder has always remained open through

Cadwalader Park. After the canal had been

officially abandoned in 1933, the D&R Canal

property in Trenton was deeded first to the state

and, in 1936, to the city. Later, the D & R was

adapted for use as a water supply system. The

end of the canal era and the conversion of

Ellarslie, both hastened by WPA projects, further

transformed the nineteenth-century character of

Cadwalader Park.

| Top | Master Plan Contents |

CADWALADER PARK (MIDCENTURY) The call for scrap metals during World War II

resulted in the loss of the park’s cast iron perimeter

fencing (Figure 21). The quantity of fencing

removed and the locations from where it was

taken are unknown, but the metal fixtures in the

park today postdate the war period. With the

war’s end, visitor use increased. A concession for

children’s pony rides was granted in 1943, to be

followed after the war by one for small mechanical

amusement rides (1951). Widespread automobile

use marked the beginning of a new era in |

Figure 21. Trenton Times photograph of scrap metal drive in the park during World War II |

Ball fields, tennis courts and basketball courts were constructed on both sides of Lovers’ Lane, around 1967. A comfort station was built in the upper park, in 1968, to serve a new Babe Ruth baseball field. The traffic circle at the Parkside entrance was enlarged to direct the flow of vehicles into the park. A CETA grant paid for walkways to Ellarslie, a replacement (though much smaller) picnic pavilion in 1982, and a new canal bridge.

Historic Preservation

Cadwalader Park felt the impact of the historic

preservation initiatives that began in the 1970s.

Ellarslie, which had deteriorated due to its use as

a monkey house, was named to the National

Register in 1973. The nomination, which included

all of Cadwalader Park, stated that Ellarslie

“retains the major portion of the landscape,

which was an integral part of Notman’s planning

for such suburban or country villas.” Restoration

began in 1978 for the mansion’s new use as a city

art museum. Cadwalader’s contributing historic

resources, representing a period of significance

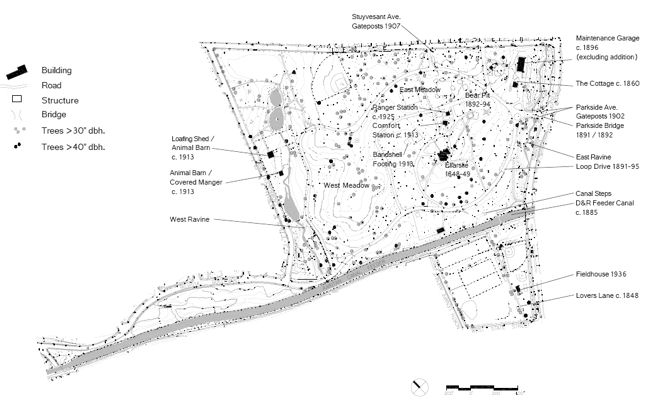

from 1848 to 1936, are illustrated in Figure 22.

The Friends of Cadwalader Park was organized in

1980 to raise money and perform tree maintenance

for the park’s restoration. The Friends also

objected (in vain) to the CETA-funded picnic

pavilion built in 1982 because it did not match

the scale or design character of the original

“Grand Lodge” pavilion.

Figure 22. Contributing Historic Resources

End of an Era

Toward the end of this period, the gradual

decline of the park began to receive attention in

the local press. A feature article in the Sunday

edition of the Trenton Times on May 18, 1980

noted that a loss of park amenities, decreased

maintenance, and changes in use had resulted in a

park that was “fraying at its edges.” Gone were

the canoeing, the pony rides, the kiddie rides, the

balloon seller at the Parkside entry, the pedal

boats, and the plays and concerts at the

bandshell. The greenhouse was abandoned and

the bandshell was not reconstructed after it

burned down in the early 1960s. Needed

improvements to the drainage system, eroding

canal banks, and buildings went undone.

Funding for the park’s tree crew was lost and

cutbacks in overall maintenance personnel during the 1970s allowed for little more than trash

pickup and lawn mowing.

The park remained extremely popular with the community. Spectators flocked by the thousands to the summer league basketball games. Cars jammed the park roads on the weekends and the park rocked to “the beat of disco and rhythm and blues from car radios.” Then-park superintendent Harry Baum noted that grass was retreating from road shoulders. “If there are 200 cars there, 199 of them will have two wheels on the grass. That doesn’t help the situation.” Cadwalader Park was, in effect, being loved to death.